Posted December 8, 2009

My earliest recollection of hearing a Doors song was at the wedding of some people we knew in the church circles my family moved in. As near as I can piece together, the wedding took place sometime in 1970. I was all of around 11 years old and really hadn’t broadened my scope of music beyond the occasional Elvis record. But during that particular wedding, I was introduced to Jim Morrison and the Doors.

My earliest recollection of hearing a Doors song was at the wedding of some people we knew in the church circles my family moved in. As near as I can piece together, the wedding took place sometime in 1970. I was all of around 11 years old and really hadn’t broadened my scope of music beyond the occasional Elvis record. But during that particular wedding, I was introduced to Jim Morrison and the Doors.

The groom was, and is, a very gifted composer and singer of gospel music. One of the aspects of the marriage ceremony was a song that he arranged and recorded that was played at a certain part of the vows. I can’t tell you much about the rest of the song he sang to his bride, but I distinctly remember that in the middle of the medley the groom so seamlessly strung together were these lines from The Doors’ “Touch Me”:

I'm gonna love you

Till the heavens stop the rain

I'm gonna love you

Till the stars fall from the sky for you and I

I'm gonna love you

Till the heavens stop the rain

I'm gonna love you

Till the stars fall from the sky for you and I

For some strange reason, that one section of the song stuck in my prepubescent brain. Go figure. I do know that the groom went on to become an award-winning gospel songwriter and producer who produced some of the biggest names in gospel music in the 70’s and early 80’s. One of his songs was even sung at Elvis’ funeral.

But I digress.

The same year that the above-mentioned wedding occurred, another solemn Celtic marriage ceremony took place, which also involved the name Jim Morrison. In fact, it actually involved Jim Morrison and a young lady that he met and fell in love with, by the name of Patricia Kennealy, a noted rock critic who blazed the trail for women in a vocation dominated up to that point by men.

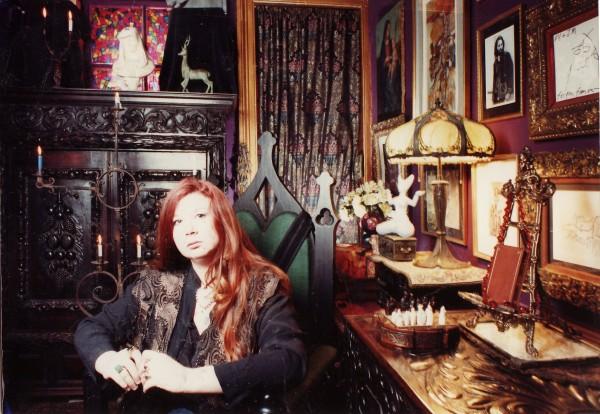

Ms. Kennealy was not only a gifted writer but was, and is, a priestess in a Celtic Pagan tradition. It was while interviewing Morrison for the magazine she edited and wrote for, Jazz and Pop, that an intellectually based friendship began, which led to a passionate romance. On June 24, 1970, they sealed their commitment to one another in a Celtic Pagan ceremony known as handfasting.

Patricia Kennealy-Morrison shares her story of her relationship with Jim Morrison in her memoir, Strange Days. Her chronicles have resulted in a tremendous amount of criticism and ridicule. One doesn’t sense that the battles with her detractors have worn her down. On the contrary, it’s apparent that she has only become stronger, as well as more determined and resolute, in her convictions and story with regards to her relationship with Morrison. Regardless of one’s opinion of what she has to say, it cannot be said that she has withered from the attacks that she has withstood.

Her character is portrayed (inaccurately, according to both her and, believe it or not, Oliver Stone himself) in Stone’s 1991 movie “The Doors” by actress Kathleen Quinlan, and the handfasting ceremony is actually performed by Patricia in the movie. But to get Kennealy-Morrison’s perspective of the vows and everything involved, you’ll want to read Strange Days yourself.

I recently approached Ms. Kennealy-Morrison for an interview and she happily obliged. She’s a very intelligent person to converse with and has very strong, definite views —some of which she shared during our chats. We eventually discussed her relationship with Morrison, of course, but I started off by asking about the most recent series of books she’s authored, “The Rock and Roll Murders.”

She explains, “They’re a series of murder mysteries set in the Sixties, at rock venues and events, some real, some fictional: murder at the Fillmore East, murder at Woodstock, murder aboard a rock festival train, murder at Abbey Road studios. The first one is Ungrateful Dead: Murder at the Fillmore, the second is California Screamin’: Murder at Monterey Pop; the third, out in December 2009, is Love Him Madly: Murder at the Whisky. The fourth, which I’m working on at the moment and hope to release in spring of 2010, will be A Hard Slay’s Night: Murder at the Royal Albert Hall.

“The young protagonist is Rennie Stride, a newspaper reporter (something I never was, and kind of regret) who seems to be the Angel of Death’s groupie, at least where rock death is concerned. Everywhere she goes, somebody turns up dead, and she has to check it out. She’s not a detective, so that’s a little limiting, but as a reporter she can ask questions and poke around in ways that cops can’t, and she’s very, very observant.

“Her mandatory sidekick is Prax McKenna, a bi superstar who’s a kind of combo Janis Joplin/Grace Slick clone, and the mandatory love interest is Turk Wayland, another superstar, an Eric Clapton clone, only without the drug problems.

“As you can probably tell, I’m having big fun with these.”

With the infamous scenes and provocative titles, I couldn’t resist asking if there were any “veiled truths” woven into the plots.

“Not really. All the ‘truths’, such as they are, are pretty naked. Good ones and less good ones alike. The characters, of course, are fictional. Rennie is not me, and Turk is certainly not Jim. And back in the actual day, there weren’t any big dramatic rock murders of the sort I cook up.

“But the band dynamics, the record company rip-offs, the personal stuff: that’s all very real indeed. And a lot of it was not very nice —which makes it absolutely perfect for the series.”

While on the subject of writing, I got into the topic of her book Strange Days, published in 1992, a year after Oliver Stone came out with his Doors movie. It’s a riveting work that covers virtually every aspect of her relationship with Jim Morrison. I asked her what the reaction to the book was.

“Thank you for appreciating it. Well, reaction depends on who you are, and if you’re too smart to have fallen for the ‘Ballad of Jim and Pam’ that assorted ignoramuses and apologists and people with personal and money-driven agendas have tried to cram down the public’s throat for the past 40 years.

“Most people with half a brain realized long ago that Jim couldn’t possibly have been the drunk, drug-besotted creature that his (male) biographers put out there for public consumption. Where would the songs and poems have come from, if he was stoned all the time? Short answer: they wouldn’t and he wasn’t.

“Days got very good reviews, except from a few morons with personal axes to grind at my expense. But readers were thrilled, at least many thousands of them have told me so, to hear what Jim was really like, and that he had a real relationship with someone who was on his own level, and who wouldn’t take crap from him or play games but called him on his B.S. and loved him enough to tell him…someone whom he loved enough to marry. And anyone who read some of my reviews of his work and still wanted to put a wedding ring on my finger was not only a man in love but a very brave man indeed.”

The marriage. Of all aspects of her story about her relationship with Morrison, this is arguably the one event over which she receives the most heat from her critics. Among the more serious Doors fans, there are those who side with Patricia that the ceremony legitimately and legally wedded her to Morrison, and there are those who don’t agree and challenge her from a variety of perspectives, the most consistent one being that the marriage wasn’t legally recognized.

It’s on that point that I ask Patricia how she answers her critics. Her response is lengthy and detailed.

“Actually, according to New York State case law, our marriage could be considered a valid one. There was a court case, Persaud vs. Balram, in which a Hindu man sought to have himself declared never married because he and his wife had not obtained a marriage license and because the Hindu priest who performed their purely religious ceremony, before witnesses, was not authorized to perform marriages in New York State.

“Well, the judge ruled that the man was indeed married, that his marriage had been a legal one despite those issues, and if he wanted to be lawfully shed of his wife he would have to go through a legal divorce like everybody else.

“Jim and I were in a similar situation: we too had no license and the ceremony was a purely religious one, though carried out by a Presbyterian minister empowered to perform marriages in NY State.

“So, according to this case (which two separate lawyers have brought to my attention), and this wasn’t the only one or even the first one, I consider that Jim and I were married. I simply choose not to pursue it and take it to court, because I don't want people's mucky hands all over our private life, because I don't grub in the gutter for money, and because I want to protect the identities of the officiant and witness. And most importantly, because I want to protect Jim’s and my privacy, the few scraps of it we still have left. There are things in my possession which Jim is the last person to have touched, apart from me, and they’re going to stay that way.

“The signed marriage paper [reproduced in Strange Days] isn't the only piece of documentation I have. There are letters and poems from Jim in which he refers to me as Mrs. James Morrison, his wife and other such titles—in his own handwriting—things his own family has seen.

“So yes, I think I do have grounds to consider myself Jim's spouse, and anyone who says otherwise can go to hell. Jim said I was his wife, and that's more than enough for me. And he should know who his wife is. Plus, how disrespectful is that kind of attitude of Jim himself? I’m the Yoko Ono of the Doors, and I’m very weary of being treated that way when all I have ever done for Jim has been out of love.

“On the other hand, it’s also rather telling that neither the Morrison family nor the Courson family, in the almost 18 years since Strange Days appeared or the almost 30 years since No One Here Gets Out Alive (which said publicly in print, for the first time, and I quote, ‘Jim and Patricia were married’), ever made any attempt to prevent me from using the words wife, marriage or the name Morrison, which I have used privately ever since June 24, 1970 and assumed legally in 1979, after I left the music business.

“If they didn't in all this time seek to stop me, I have to assume they just don't care...or, perhaps, their legal advisors were aware of the case law and didn't want the hassle of another court fight, which, based on New York State law at least, they might very well lose. I’ve never been in it for the money and I never accepted a cent from Jim, except once in a situation that was his rightful responsibility, so that’s not even an issue for me.

“Maybe they figure it’s easier and more effective to discredit me by ridicule. Well, for my husband and myself, I can take it. This is the most I’ve ever said publicly about this. And that’s all I’m going to say.”

Bringing the conversation back to her book, Patricia went on to say that intelligent readers got what she had to say and saw through the ‘romanticization’ of Morrison’s relationship with Pamela Courson. A relationship “that, in the end, had become little more than a comfortable, non-sexual (they both told me so) relationship between two addicts and mutual enablers. Jim’s and my relationship was one of a young man and a younger woman who had a great romantic, intellectual and sexual partnership. And people—the right people—recognize this.

“Listen, I’ve never denied the importance of others in Jim’s life—and I’ve certainly never denied Pam’s importance— yet people, many of whom weren’t even alive then, deny my importance in his life all the time. Others in Jim’s life, and many who never even knew him, make a big deal of how much they loved him, yet they write endless books or plays or movies that profit off him; they even sell his possessions for money, which I would sooner starve in the gutter than do.

“Yet when I speak of how desperately much I love him, of how I’ve stayed stainlessly faithful to him for forty years and will to the end of my days, of my unending grief and loss, somehow that doesn’t count, and my writing ONE book, as opposed to their Morrison cottage industry, the only book that really shows him the way he was and has insights nobody else can match, somehow I’m Satan’s concubine for doing that. How is it okay for them to endlessly make money off Jim, but not okay for me to have written a single book about him—a book which was also about me and which, though it sold well, has hardly made me a wealthy woman? Well, that’s hideously cruel, hypocritical and unfair, and Jim would be the first person to say so.

“He was quoted as having once told Danny Sugerman that if his, Jim’s, name could ever buy Danny a cup of coffee, Danny shouldn’t hesitate to use it. And as we all know, Danny never hesitated for a heartbeat to capitalize on Jim. How is that more honorable than what I’ve done for Jim, at great personal cost to us both, with Strange Days? I’ve kept the faith better, and done better by Jim, and more lovingly, than just about all of them.”

Writers often wish that they had said, or not said, something in their work. I asked Kennealy-Morrison if there was anything she wrote in Days that she wished later that she hadn’t.

“Nope. It all had to be there. If the bad stuff wasn’t there, nobody would believe the good stuff. And there’s a lot of good stuff that people really should be believing, stuff they’re not getting anywhere else. If I didn’t include it all, I’d be as bad as Oliver Stone. Worse, because I know better. Anyway, it’s my story as well as Jim’s, half of it mine and half of it his, and I have every right to write about it.”

Was there anything she wished that she had either written about or provided more detail in the book? Her response is even more firm and very much to the point.

“Again nope. Well, maybe I wish I’d been even harder on the idiots who are so hard on me. They weren’t there. Or if they were, they still don’t know and they have absolutely no business saying what they say. All they can legitimately say is that they don’t know. Jim kept his life very compartmentalized, to protect his own privacy and that of the people he cared about. The naysayers haven’t seen the proofs I’ve got. The people who have, or even just the people with a brain, have no problem whatsoever believing and accepting what I have to say. Because it makes sense. Why would anyone who truly admires Jim want to take the word of biographers and groupies who trash him and make him look like a buffoon, and not listen to the one person who’s telling them of his dignity and beauty and intelligence and courage and grace of spirit? What kind of fan is that?

“The ones who are still strip-mining Jim’s life and legend to this day, movie makers and writers and such, have chosen to go with the official party line, and they don’t often bother to consult me. They just don’t want to hear what I have to tell them. They prefer their own, utterly erroneous take on it. And I just can’t imagine why. The truth is so much better and more beautiful.

“Bottom line, why the hell would I, already a successful and respected author with a fan following of my own, put myself and my love for Jim out there as a target for their cheap and unspeakably hateful shots, for forty years, if it wasn’t the complete and utter truth? Nobody’s that much of a masochist.”

Since she mentioned that others have Morrison all wrong, I asked her what would be the one thing that she feels has been least covered and understood about him. Without hesitation, she cut right to the chase, with multiple points.

“His desire not to be an icon. Jim was one of the great iconoclasts of all time, one of the great image-breakers, as I’ve said many times. He’d hate what people have made of him.

“Also his humanity. People project their unsavory fantasies and wish-fulfillment trips onto him, and he doesn’t deserve it. They did it when he was alive, and a million times more so since he’s been dead. He was a beautiful, courteous, intelligent, sweet, generous, humorous, loving soul. But the Doorzoids and Pambots don’t want to hear that. I’d say that’s their loss, but really the loss is, tragically, Jim’s.”

In Strange Days, Patricia muses about what Morrison would have accomplished had he not died in Paris in 1971. Since almost 18 years have passed since the book was published, I asked her if she would mind speculating as to what she thought he would have accomplished or progressed to.

“Well, I very much doubt he’d still be on tour with John, Manzarek and Krieger, if that’s what you’re wondering! [I was.]

“I would imagine he’d have turned full-time to writing and film-making. He’d probably never have abandoned music completely, because he loved it too much; in fact, he’d asked me to look into New York studios and engineers, for when he came back from Paris to live with me here, and his plan was to record a solo album. But by the end, he truly believed music hadn’t served him well—or at least that fame and stardom hadn’t served him well—and he desperately wanted out of it. And, well, he got his wish.”

What would blow Jim’s mind the most about today’s music?

“How artificial, colorless, stupid, boring, trivial, shallow and talentless it is. He’d hate it.”

Ouch!

In the years following Jim Morrison’s untimely death, there were bitter legal battles over his estate. Ultimately, Pamela Courson won control of the estate shortly before she died of a heroin overdose in 1974 (after a career as a prostitute, a sad and horrific fact affirmed by even her friends and Jim’s biographers). The estate was jointly managed by her parents and Morrison’s parents, until Morrison’s parents passed away (his mother in 2005 and his father in December, 2008). Does Kennealy-Morrison have any comments about the estate and its impact on Morrison’s legacy?

“I have nothing to do with it. Pam’s father is dead now too, so it’s just her mother left of the older generation. I have no idea how it’s handled, and I don’t particularly care.

“The one thing about the estate that does affect me and upset me is the fact that I will probably never be able to publish the many unpublished poems, letters, songs and drawings Jim left with me. According to current law (though that’s changing), they’re all considered part of his literary estate. I own the physical material, but not the publishing rights. I could sell them, or eat them, or even exhibit them, but I can’t publish them. I’d actually have to ask the estate’s permission to publish. To publish my own private love letters, written for me and given to me by the man I love, the man who loved me back! But I haven’t given up hope, though; at least not yet.

“They’re achingly beautiful, gorgeous, loving words, some of it ‘jaw-droppingly erotic’, as a London reporter, to whom I’d shown a number of pieces, wrote in her feature article—very hot stuff indeed, and why wouldn’t it be, we had a very passionate relationship—and the poems were clearly evolving into real worth, as a poet friend of Jim’s who’s also seen some of it said. Other people who actually knew Jim have seen a lot of the material, including family members and friends, so they know. It’s a great pity and shame that Jim’s fans will probably never have that privilege.

“I had planned to call the book Fireheart: The True Lost Writings of James Douglas Morrison, with extensive comment and annotations by me, and publish it 50 years after Jim’s death, when copyright constraints would be up. Unfortunately, Sonny Bono and Walt Disney shoved through an amendment to the copyright law, so now it’s 75 years and we’ll probably never see it. Thanks a lot, guys!”

What a treasure trove those documents would be!

For years there has been speculation that Jim Morrison never actually died but went into seclusion with a new identity and a new life. What does Patricia have to say about such theories?

“Anyone who doesn’t believe Jim Morrison is dead is too stupid to be allowed to live.”

Not wanting to be considered one of the stupid, I change the subject to the fact that Kennealy-Morrison was a pioneer in the realm of female rock critics, to which she responds, “It was a boys’ club then, a seething cesspit of male chauvinism. There weren’t many women around, and I was the only one who was not only a working, writing critic but the editor of a national magazine [Jazz & Pop].

“You got tarred with the groupie brush, especially if you were in the least bit attractive. That, unfortunately, was the kind of thing female rock writers ran into all the time. You had to be twice as tough as the guys to get through it and do your job. Jim, to his credit, was ever the gentleman and the professional."

Does Patricia have a current female rock critic who commands her attention?

“I have no idea who’s a rock critic these days, male or female. I don’t bother to keep up with it, since I loathe the ‘music’. Pretty much the only rock critic I've read recently is Steve Hochman, formerly of the Los Angeles Times and now with his own column online. And from time to time, people I knew in the old days. Otherwise, though, not so much.”

Surely she’s seeing some positive changes in rock journalism?

“I haven’t read rock journalism since the mid-70s, so I really couldn’t say. I know that many more women got into it after me, so of course I think that’s a very good thing. And I’m quite proud of having been a pioneer and a groundbreaker, though I don’t get much credit for it —credit which, by the way, I feel I absolutely deserve.”

What are some of the negative changes Patricia sees today?

“Oh, just speculating, but it’s probably all puffery. Back in the Sixties, rock critics and journalists were in some senses almost co-creators with the artists, or, if that sounds too conceited, at least interpreters and apostles and proselytizers. Missionaries, even. Today, nobody wants to actually criticize anything, heaven forbid. But then, there’s really nothing creative there to criticize. It’s just commercial, artificial, record-company-generated trash.”

Double ouch!

I later asked Ms. Kennealy-Morrison where she saw rock journalism heading. I wasn’t expecting a positive outlook from her, and she didn’t disappoint me.

“It’s dead. Long ago, Jim said rock was dead, and now I say rock journalism’s dead, and has been for decades.”

Expecting a similar response, I still had to ask her if there are any artists or bands that are commanding her attention today.

“I don’t listen. Every now and then I’ll hear something startlingly good, on a movie soundtrack or as incidental music to a TV show, and I even buy it on iTunes: Piers Faccini, Susan Enan, Lenka, Sufjan Stevens, among others. But the cuts never seem to translate into good albums. It’s usually just the one brilliant song, cherry-picked by ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ or ‘Bones’ or ‘House’ or whatever, and the rest just don’t hold up. I haven’t got the time, nor indeed the inclination, to sift through everything else.”

Still in “dumb question” mode, I asked her if she thought the music produced today has the same kind of meat and substance that our music from the 60’s and 70’s had. I duck for the answer.

“Of course not! How could it? The socio-political-cultural substrate that gave our music its weight and grace and heft and beauty isn’t there for it to take root in. The talent isn’t there either. Where’s the present-day Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison, Lennon? They’re not here, and neither are the heirs and successors they should have had. All I see is prancing nitwits who can’t sing or write a decent lyric and troglodyte strummers who robotically thud out the same three chords because they can’t play anything else—posers who just want to be celebrities. They don’t give a damn about being artists.

“There isn’t anyone alive today who even comes close to having the musical chops that our artists did. If they’re out there, good luck to them, because we’ll never hear them. That kind of art and artistry will never be seen again. It’s why I listen in the past—Airplane, Big Brother, Cream, Ventures, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Kinks, Dead, Beatles, Who, early Stones, Hollies, Four Seasons, Everly Brothers, Dusty Springfield, Sandy Bull, many, many more; or to the artists from then who are still around and still making real music—Eric Clapton, Patti Smith; or to Celtic or folk-rock artists like Alan Stivell, Loreena McKennitt, Altan, Tannahill Weavers, my friends Steeleye Span. I don’t listen to the Doors, or very, very seldom, like one track every few years; it’s just too painful to hear Jim’s voice. Which is sad, because when he died, not only did I lose the love of my life, I lost my artist-hero of all time, and I loved his music before I loved him.”

As a journalist, Kennealy-Morrison covered Woodstock, and shared her feelings about the festival in Strange Days. I asked if she had any further thoughts about the event. Again, with her acerbic wit, she answers.

“A murder or two might have made it more interesting— at least it will in the mystery novel I’m currently working on about it! But nobody played well at Woodstock. I think it was Pete Townshend who said that he always knows when people are lying about having been at Woodstock, because the people who weren’t there all say how great the music was and the people who were there all say how horrible the music was. He’s absolutely right.”

STILL stuck on stupid, I asked her if she went to any of the reunion events and if she thought the idealism promoted at Woodstock was ever achieved.

“Certainly not! It was bad enough having been at the original.” As for the idealism, “It never happened apart from those three days, and not really even then. It’s mostly autohype: sure, no violence for three days, but people were too stoned to even move, let alone beat up on their neighbor, so not as admirable as all that. Sorry if that sounds cynical, but I felt that way even as I was sitting there in the middle of it, in the performers’ pavilion with a performer’s stage pass around my neck, and I feel that way now.”

Shifting into a slightly less masochistic line of questioning, I asked Patricia what her plans are for the next five years and what can her readership expect from her.

” Oh, more rock mysteries, for sure. I have plans for at least eight more, reaching to around 1971, which I consider the end of the Sixties, with Jim’s death and the Concert for Bangladesh, on a personal and professional level respectively.

“I’d also like to get back to my Celtic science-fantasy series, The Keltiad, for two more books, just to complete the series and give everybody a nice solid ending and send-off, readers and characters alike. And there’s a Viking book I want to finish writing, a historical novel set in the ninth century.

“There’s also some effort being put into trying to sell the Rennie books as a cable TV series. We’ll see how that goes.

“But all that should, I think, see me out. I plan to die writing. Hopefully they’ll find me slumped dead over the laptop. Not a bad way to go.” To die doing what we all love to do is, indeed, a great way to go.

After completing the interview with Patricia Kennealy-Morrison, I took time to reflect on everything that I have read by, and about, her as well as everything she shared in the interview. After a lot of thought and reflection, I break down my thoughts and opinions into two categories: those who knew Jim and know Patricia and those of us who don’t. I’ll start with the latter.

To those of us who don’t know Patricia and didn’t know Jim, the bottom line is that our opinions really don’t matter. I’ll put myself at the top of that list. At the end of the day, we’re observers and readers of the stories of the players in the play. You don’t go along with the story Ms. Kennealy-Morrison shares? Fine. She will add you to her list of whom she considers ignoramuses. You do go along with her story? I think she would say, “But of course! It’s the truth and you get it!”

The other category of observation is reading the reactions to Patricia’s story from others who knew, or claimed to have known, Morrison. It’s clear that this group is motivated by one of two forces: either a continuing love for Jim and his legacy or greed to profit from it. I’ll focus on the former. The latter is self-evident.

No doubt, from what I’ve pieced together from what I’ve read about Morrison, he would be amused and maybe saddened by the infighting among those who have loved him with an obviously deep and sincere love, romantically or brotherly. But in the end, he would, no doubt, revel in the love expressed.

Both types of love are rooted in their interactions with the man that have left each of those people feeling that they have a unique insight into this complex, multi-dimensional man. Patricia Kennealy-Morrison provides a very intimate peek into a part of her relationship with Jim Morrison. She likely has many more gems in her treasure chest of memories of her brief time with this iconoclast of rock and poetry. This relationship, as with others whose lives intersected with his, left her life forever changed and with memories that she cannot nor wants to escape from. And, by telling her story, she has elected to open herself up to vicious attacks and ridicule as well as to respect and admiration.

Has she profited from her story? Perhaps, but I doubt that she’s made herself rich from offering the world a glimpse into the previously mentioned treasure chest. The gratification of sharing this small section of her life with the world far outweighs any money that she could possibly receive from telling it. That said, I’ll wager that whatever money she may have made from book sales and from participating in the Oliver Stone film, the pain from the withering attacks far outweighs any money she may have earned from her tale.

Perhaps she is taking as her own the words Morrison sang in another line from the song I quoted at the beginning, “Touch Me”, wherein he sings, “Can’t you see that I am not afraid?”